Some simple rules to un-dumb your entertainment journalism

Dispatches from an art form in decline

After the past week’s worth of news, this one feels like it needs a bit of context-setting, or at least a tone-setting preamble. Let’s go:

I was by no means a deep fan (or, anti-fan) of Rob Reiner’s work. I mostly just thought he was one of those fun Hollywood guys who would always be there. I liked him. He seemed generous.

No one is always gonna be there, of course, but (much like with Hackman, earlier this year), the horror of how Reiner and his wife met their end has devastated me in ways that have little to do with any feelings I have about him as a creator.

And yes — horrible shit like that happens all the time, in that horrible country and every other one. Don’t be a dick about it: you know it feels different when it’s someone you, even parasocially, liked.

As for the Warner Brothers / Netflix / Psky thing, any comments I make, have made, or will make re: the best of a bunch of bad options, should be taken with a couple of gigantic grains of salt, which longtime readers (and erstwhile listeners of the Mamo! podcast) would probably already know:

Grain 1: theatrical moviegoing as a cultural force has been squeezed out of relevance and into niche for at least the past fifteen years, and inflection points like the streaming wars, the pandemic, or now this, only make visible the gradual process that has been underlying the majority of the years of this century. Don’t expect me to mourn the viability of my favourite art form for the entirety of two slow decades. I mourned it in 2010, and in many podcast episodes afterwards. A lot of y’all got in the comments to tell me I was crazy. Enjoy that self-righteousness.

Grain 2: unregulated late capitalism is a civilization-sucking malevolent force that is ruining literally everything; to expect Hollywood of all fucking places to be exempt is just pitiably naive. A half-dozen American multibillionaires simply should not be allowed to do what they are doing, full stop. The only way to stop them is through the enacting of, or enforcement of, laws. That they are not being stopped is, tacitly, a much larger problem than just “nooooooo we want moooooooovies,” and it needs to be addressed at a much higher level — one which, if I were to add a grain 2.5 here, is never coming. United States, you must unfuck yourself, but you’re not gonna, so see above re: grain 1.

On with the show.

Eight simple rules to un-dumb your entertainment journalism

As you may know (or not know, in which case… bless you), I got hooked on A.R. Moxon’s LOST writeups in mid-course last year. (I think I came in around issue #37.)

Don’t worry: this piece isn’t really going to be about LOST. Or at least, you don’t need to know any more about LOST than you already know (even if you’ve never watched the show) to understand what I’ll be describing.

Anyway. I came into Moxon’s recaps around issue 37, and then at some point in the last few months I was like, “wait, shit, I don’t understand the understory of these pieces,” i.e. their fundamental premise and argument, so I went back a few instalments to try to figure it out. And then I ended up going all the way back to the beginning and working my way forward in full. Which, one could argue, is the most logical way to read an argument.

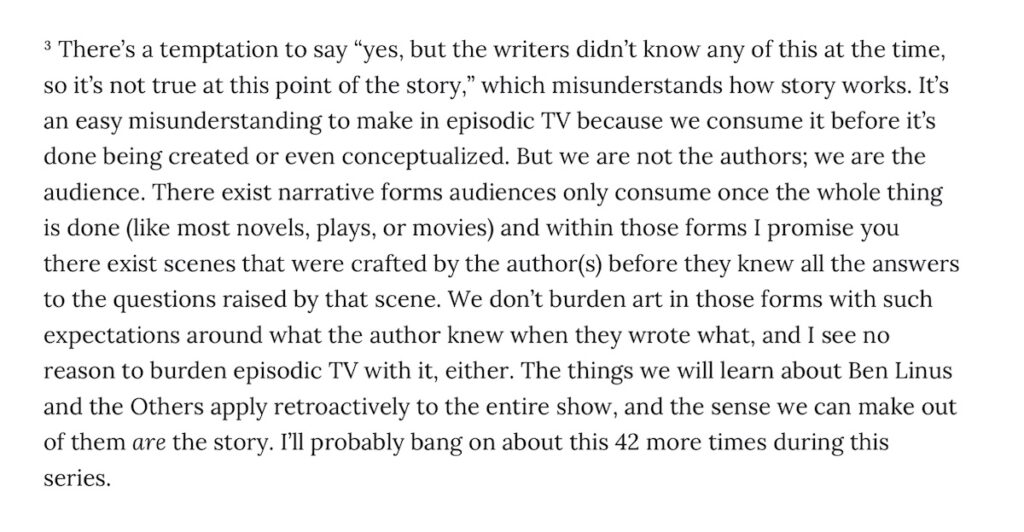

There are a lot of arguments in Moxon’s pieces, some of which are gadzooks-bonkers (complimentary). Given it’s LOST, though, one of the big obvious ones is: did the writers know what they’re doing, or were they just making it up as they went along?

Popular opinion, at least in the snarkier / Reddit-er parts of the internet, trends to the latter. Moxon, unsurprisingly given he’s doing all of this in the first place, is pretty firmly “fuck you” on that whole line of thinking, and on those lost sheep who think it.

As I said, this comes up a lot in his pieces, but here’s a particularly emblematic footnote that (I think) describes his thinking in full:

Obviously, as process wonk, I like that quite a bit. I like it so much, in fact, that it made me begin to (mentally) side-eye a lot of the television criticism and entertainment journalism I regularly consume.

Now, I understand such journalism. It isn’t there — at least, from a top-down perspective, it isn’t there — to be “thoughtful” or “useful” or “good.” It’s only there to generate clicks.

So if critic after critic falls into the trap of adoring a new show they’ve been sent the first four episodes of in advance, and then wondering later on in their week-by-week coverage “wait a minute… is this show maybe actually not good [because I don’t see where it’s going as of episode 11 of 46]?”, only turn that narrative around again when the show does something else interesting, as though a television production were undergoing some kind of redemption arc… well, those writers are serving the algorithm. Good for them, lah-dee-dah.

But I’d say it suggests rule #1:

Rule #1: Individual segments of serial work cannot, every time, serve as referenda on the success of the work as a whole. Call it the Marvel Cinematic Universe Rule™️: every single Marvel movie cannot be the one where you hold forth on whether Marvel movies are “good anymore.”

There’s a bit of form vs. function here, which I like. Obviously — in TV or serialized film — there is a requirement that discrete episodes work on their own terms, while also serving the creative aims of the greater whole. My point would largely be that one needs to pay attention to both elements of the construction simultaneously; not solely the one that is in front of you; and not solely the larger one that is not in front of you in its entirety (yet).

This reminds me of a longstanding peeve of mine:

Rule #2: Use caution when applying critical thinking to genres intended for different audiences. Call it the Star Wars Rebels Rule™️: it means, if you feel like the consequences of genocide aren’t treated with enough nuance and depth for your liking in a literal children’s cartoon, feel free to tell me why, but understand that you’re demonstrating a fundamental misunderstanding of the connection between form and function.

More broadly, this just means that different genres approach metaphor in different ways. We’re a very literal-minded species, particularly in the west, so sometimes, metaphor does our head in. Angel and Spike on Buffy the Vampire Slayer, for example, are great instances of characters initially presented in highly metaphoric guises who, over the course of the series’ long term, become wrapped in conflicting real-world nuance to the point where their metaphors don’t really work anymore. Is that good? Is that bad? I dunno, but it’s not something you can just ignore.

Or, in the childrens’ cartoon example, the creative team is called upon to narrate in a mode that is accessible to their audience, i.e. children, not the adults writing the criticism. This doesn’t mean it mustn’t also be good — more on that whole misunderstanding another time — only that its treatment is necessarily applied differently.

Let’s bang out a few more rules, rapid-fire:

Rule #3: Stop Cinema Sinsing, everywhere and everything. Stop quibbling about continuity except where it directly impacts narrative. Stop stopping critical thinking dead, whenever you can't work out what year a part of the story takes place in. Stop walking in with snark. Does it work emotionally, on first viewing? Is it serving the narrative momentum, in the moment? 'Nuff said. (If you can't answer the question re: working emotionally, you shouldn't be a critic. Sorry.)

Rule #4: the 98% rule. Basically this boils down to: consider the mass market. One of the reasons theatrical moviegoing has become niche is that 98% of the general public doesn’t give a fuck. Nothing, and I mean nothing, you are writing about matters broadly, if it doesn’t matter to that 98%. That’s fine! All art needs critical thinking. But enough with the “why is no one talking about this??!” framing, when the simple, obvious answer is: because 98% of the audience doesn’t give a fuck.

Rule #5: Stop fighting the last war. Currently, the last war is A.I. Sorry folks: again using the 98% rule, 98% of the people you are complaining to about generative A.I. feel the same about ChatGPT as they do about motion smoothing on their TV, i.e. "...whaaaattttt?" This is not me saying that we should just accept A.I. slop, or the hucksters who push it. The whole thing is garbage, but it's already here. Like Trump, A.I. is a symptom of a diseased culture, not a cause. What do you have to say about that?

Rule #6: Stop writing worst-of lists. I know, I know, your editor insists. Well fine: if you’re being paid to do it, go for it. If you’re not: you’re just making things worse. Seriously.

Rule #7: Stop referencing Harry Potter. She sucks, and her ideas suck. (This probably also applies to “stop referencing Star Wars” but if I did, I’d have to fold up the newsletter. Sorry!)

Rule #8: Ride the wind less. Be the wind more.